<< Back

Meet the Heart’s Lieutenants: 4 Valves That Keep Your Blood Moving

February 14, 2019

The heart gets all the glory as the hardest-working human organ and, with 80 million beats a year and up to 6 billion beats in the average lifetime, who’s going to argue?

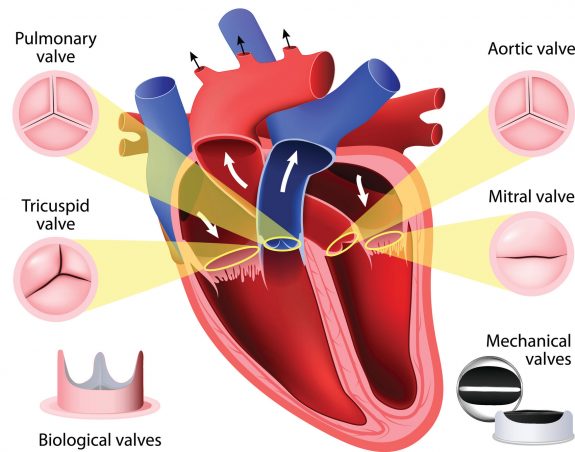

But today let’s acknowledge, in a best-supporting role, the heart’s four valves — the mitral, tricuspid, aortic and pulmonary — that control blood flow in and out of the organ. The mitral and tricuspid valve direct blood flow from the two atria (upper chambers) to the two ventricles (lower chambers). The aortic and pulmonary direct blood out of the ventricles. Together, they carry deoxygenated blood from the body and push oxygenated blood back into the body.

Yes, these four valves made of tissue flex with every single heartbeat, a lifelong demonstration of endurance, strength and pliability. Yet no one knows unless something goes wrong. It’s no coincidence that the only national recognition they receive each year is National Heart Valve Disease Day (Feb. 22), an acknowledgment that up to 11 million Americans have the disease affecting one or more of the valves.

Here are some causes of heart valve disease:

- High blood pressure and heart failure.

- A damaged heart caused by injury or heart attack.

- Cardiomyopathy, a disease of the heart muscle.

- A heart attack.

- A birth defect caused for unknown reasons before birth as the heart takes shape.

- Myxomatous degeneration, a weakening of the mitral valve’s connective tissue.

- Infective endocarditis, an inflammation of heart tissue caused by germs that enter the bloodstream through syringes and other medical devices or through a break in the skin or gums.

- Untreated strep throat or other strep-bacterial infections that become rheumatic fever.

- Calcium deposits and other age-related changes.

- Lupus, an autoimmune condition.

- Aortic aneurysm, a swelling of the aorta.

- Hardening of the arteries (atherosclerosis).

- Coronary artery disease (narrowing, hardening of the arteries).

- Syphilis, a sexually transmitted disease.

If your doctor suspects heart valve disease, it’s likely one of these conditions:

Regurgitation: Blood backflows into the heart’s chambers when a valve doesn’t close tightly.

Stenosis: The valve’s flaps can’t open fully because they have thickened or stiffened, preventing normal blood flow through the valve.

Atresia: When you’re born with either a missing or abnormal valve. Tricuspid atresia blocks blood from flowing to the right ventricle from the right atrium.

Extreme fatigue, shortness of breath, a heart murmur or palpitations, dizziness and swelling in the ankles, feet or stomach are among the signs of possible heart valve disease. Sometimes, heart valve disease only requires medications or lifestyle changes, such as a diet change, avoiding heavy alcohol consumption or stopping smoking.

Here some of the ways doctors at Hartford HealthCare’s Heart & Vascular Institute treat mitral valve and aortic valve disease, the most likely sources of heart valve disease.

Mitral Valve Repair

Conventional: A repair procedure is typically recommended for patients with mitral valve regurgitation, the most common heart-valve disorder.

“Preserving the valve keeps the architecture of the heart intact and the patient has much better quality of life and more longevity,” says Dr. Sabet Hashim, chairman of cardiac surgery and co-physician-in-chief of the Hartford HealthCare Heart & Vascular Institute. “The patient requires less blood thinners, they’re prone to less infections, and the function of the heart is stronger.”

MitraClip (nonsurgical): MitraClip therapy allows doctors to reach the heart through a thin tube called a catheter inserted into a vein in your leg. The MitraClip, as the name suggests, is a mesh clip no taller than a dime that attaches to your mitral valve, allowing the valve to close more securely and prevent the backflow of blood into the atrium from the ventricle. In most cases, patients are released from the hospital within three days.

Transcatheter Mitral Valve Replacement: TMVR allows doctors to replace a malfunctioning mitral valve — either the patient’s own or bioprosthetic valve from a previous surgery — using a small tube called a catheter inserted into a large vein in the groin instead of conventional open-heart surgery.

TMVR uses the same technology as the Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement, or TAVR, which places a new aortic valve within the existing valve, is also being used now in moderate-risk cases.

Aortic Valve Repair/Replacement

TAVR: Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement is a minimally invasive procedure to repair a damaged valve by inserting a replacement without removing the old, damaged one.

Doctors at Hartford HealthCare’s Heart & Vascular Institute at Hartford Hospital have performed more than 1,000 TAVR procedures, creating one of the largest programs in New England. Hartford Hospital is now one of 35 hospitals participating in a nationwide study that allows TAVR for low-risk patients. The procedure is currently approved by the Food and Administration for high-risk and intermediate-risk patients.

Recovery from a TAVR procedure is typically about a week, compared with three months for a surgical-valve replacement.

Many experts foresee TAVR, a less-invasive procedure with a success rate comparable to conventional open-heart surgery, as the eventual preferred treatment for all aortic-valve replacement patients.

For more information on heart valve disease, visit Hartford HealthCare’s Heart & Vascular Institute by clicking here.