An inflammation of the pericardium, a two-layered membrane around the heart, is known as pericarditis. The pericardium performs multiple tasks, none more critical than holding the heart in place.

The pericardium ensures the heart works properly by:

- Limiting its motion.

- Preventing overexpansion when blood volume increases.

- Lubricating the organ.

- Protecting against infections originating in other organs.

- Preventing excessive dilation during extreme volume overload.

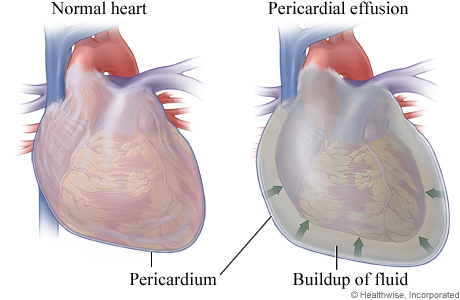

- Fluid between the pericardium’s layers acts as a shock absorber, preventing friction.

Symptoms

Pericarditis often announces itself with intense pain either in the chest’s central region or left side. Pain also might radiate to the shoulders, back, neck and abdomen. Unlike angina, a short-lived chest pain that usually responds to rest, pain caused by pericarditis can last for hours, even days, and is unaffected by rest.

The pain’s intensity might resemble a heart attack. Always call 9-1-1 when you feel such pain.

Pain caused by pericarditis is sometimes lessened by sitting up and leaning forward. Breathing deeply and lying down can worsen pain.

You might also experience:

- Fever.

- Difficulty breathing.

- Weakness.

- Heart palpitations.

- Coughing.

Chest pain is often missing in cases of chronic pericarditis. Instead, this condition is characterized by difficulty breathing, fatigue, coughing, palpitations and, in severe cases, swelling in the stomach and legs (and possibly low blood pressure).

Pressure from excess fluid in the heart's membrane, called pericardial effusion, can cause chest pain. Pericarditis usually isn’t serious, but it has two potentially dangerous complications:

Cardiac tamponade: When excess fluid collects between the pericardium’s two layers, pressuring the heart. This creates a sharp drop in blood pressure because the heart can’t fill with blood as it usually does, restricting blood outflow. Untreated, this condition can be fatal.

Chronic constrictive pericarditis: When an inflamed pericardium becomes rigid, restricting the heart’s movement. The heart then can’t fill with the appropriate amount of blood. This rare disease can lead to symptoms of heart failure.

Causes

It’s often undetermined, but pericarditis is typically caused by a viral infection. Other infections (fungal, bacterial and respiratory) can also lead to pericarditis.

Chronic pericarditis is often linked to an autoimmune disorder (rheumatoid arthritis, lupus and scleroderma), when misguided antibodies produced by the immune system attack the body’s tissues or cells. Males ages 20 to 50 are more likely to develop pericarditis.

Your doctor will also want to know if you have or had:

- A heart attack.

- Heart surgery.

- Kidney failure.

- Cancer.

- HIV/AIDS.

- Tuberculosis.

- An injury from an accident.

- Taken certain medications for blood-thinning, seizures or an irregular heartbeat.

Treatment

Initially, your doctor might proceed conservatively by recommending an over-the-counter anti-inflammatory like aspirin or ibuprofen.

Pericarditis often goes away within a couple of weeks. If it doesn’t, your doctor might prescribe a stronger medication (colchicine). When an infection causes pericarditis, it’s usually treated with an antibiotic.

If you develop cardiac tamponade, doctors might remove excess fluid in your pericardium with a procedure called pericardiocentesis, using a needle or catheter inserted into the chest wall. Removing the fluid buildup reduces pressure on the heart.

When chronic constrictive pericarditis doesn’t respond to analgesics, diuretics (for heart-failure symptoms) and antiarrhythmics (atrial fibrillation and other abnormal heart rhythms), doctors might have to remove the stiffened pericardium from the heart in a procedure called a pericardietomy.