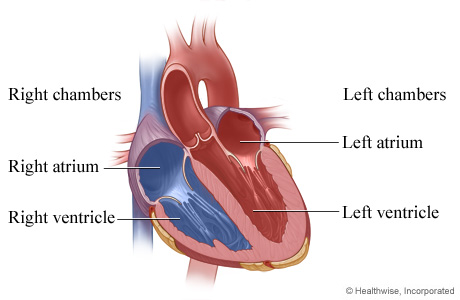

The tricuspid valve, when working properly, keeps blood flowing in the right chamber of the heart from the right atrium (top) to the right ventricle (bottom) with three leaflets, or flaps, that open and close.

When it’s not working properly, it’s likely because of one of these types of tricuspid valve disease:

Tricuspid regurgitation: Blood flows backward from the right ventricle to the right atrium when a leaky valve doesn’t close securely.

Tricuspid stenosis: Stiffened valve leaflets leave a narrowed opening that restricts blood flow. Because tricuspid stenosis is often a byproduct of inflammation caused by rheumatic fever, a disease now restricted to mostly developing countries, doctors in the United States see this condition less frequently.

Two tricuspid valve disease types present at birth (congenital):

Tricuspid atresia: The tricuspid valve is either missing or malformed, with tissue blocking blood flow. This rare congenital heart disease affects an estimated five in 100,000 live births.

Ebstein’s anomaly: The tricuspid valve’s leaflets are positioned abnormally low, causing regurgitation as blood flows backward into the right atrium instead of onward to the lungs.

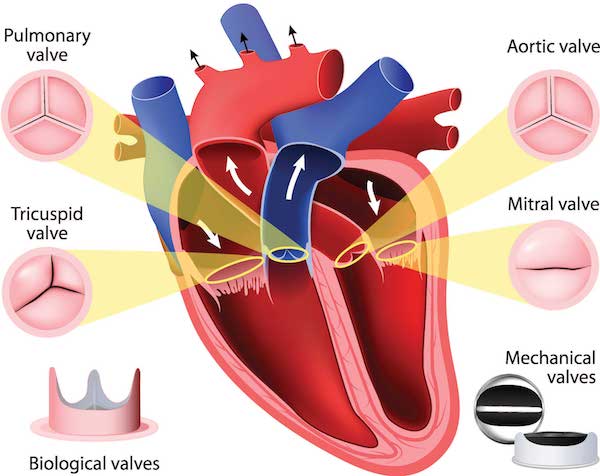

Your heart valves, with potential replacements:

Symptoms

You might not know you have tricuspid valve disease until the condition becomes severe. It’s also possible your doctor will discover the disease after requesting tests for a different condition.

Here are some symptoms.

Tricuspid valve regurgitation:

- Shortness of breath during activity.

- Fatigue.

- Swelling in ankles, feet, legs, abdomen.

- Abnormal heart rhythms (arrhythmia).

Tricuspid valve stenosis:

- Pain in upper-right abdomen.

- Enlarged liver.

- Heart palpitations.

- A fluttering sensation in the heart.

- Lethargy.

Causes

If your tricuspid valve disease is not congenital, it could be caused by heart failure (regurgitation) or a bacterial infection called infective endocarditis (stenosis).

Here are some common causes of the disease.

- Pulmonary hypertension (high blood pressure in the lung’s arteries).

- Cardiomyopathy (a weakened heart muscle).

- Heart failure.

- Heart attack.

- Heart disease.

- Infection (infective endocarditis or, rarely, rheumatic fever).

- Chest injury (blunt trauma from a car accident.

Diagnosis

There’s a good chance you won’t notice any signs of tricuspid valve disease. Your doctor might detect the first sign by listening to your heart with a stethoscope. A whooshing sound revealing a heart murmur, for instance, could indicate tricuspid valve disease

Here are tests your doctor might order:

Echocardiogram: An ultrasound test, the one most often used to diagnose tricuspid valve disease, that relies on a transducer that sends high-pitched sound waves to create moving pictures of your heart.

EKG/ECG: An electrocardiogram records the spikes and dips of your heart’s electrical activity, typically with a device connected to a laptop that stores the results.

Coronary Angiogram (Cardiac Catheterization): A technology that uses dye and special X-rays to reveal the interior of your coronary arteries. During cardiac catheterization, with small tubes in a vein or artery (in the leg, arm or neck) that reach the heart so you doctor can use blood samples and blood pressures to evaluate the organ. Because an angiogram uses more powerful X-rays than a conventional chest X-ray, doctors will perform only when it’s considered essential.

Cardiac MRI (Magnetic Resonance Imaging): Detailed images of your heart are available through an MRI’s powerful magnetic field and radio waves.

Stress Test (Exercise): A baseline test, on a treadmill, that makes your heart work increasingly harder. When the body demands more oxygen, requiring the heart to pump more blood, you doctor will see if the arteries that supply the heart get enough blood. Your heart’s activity is measured with an electrocardiogram. If abnormalities are found, a stress echocardiogram test might be ordered if your doctor suspects coronary artery disease. A stress echo, as it's called, uses ultrasound to get detailed information about the heart's four chambers.

Chest X-ray: A basic chest X-ray helps your doctor detect any abnormalities in your heart.

Chambers of the heart:

Treatment

If a malfunctioning tricuspid valve is not causing any symptoms, your doctor will continue to monitor the condition. Mild symptoms are treatable with medication.

Procedures to repair or replace a diseased tricuspid valve remain rare, with about 5,000 nationally from 2004 to 2013 -- not including patients with congenital heart disease – based on a Mayo Clinic study of the National Inpatient Sample care database

Your doctor will carefully assess whether your damaged tricuspid valve should be repaired or replaced. Chances of an open-heart procedure increase if you have both tricuspid valve disease and another heart condition that requires surgery. In that case, both conditions will be treated in a single procedure.

Repair: This is an open-heart procedure requiring great technical skill. It’s important to choose a doctor from a healthcare provider like the Heart & Vascular Institute at Hartford Hospital with extensive experience in tricuspid valve repair.

Because the valve your doctor must repair the valve with your heart stopped, a heart-lung bypass machine will circulate blood throughout your body during the procedure. Depending on the damage to your valve, your doctor could separate fused leaflets, patch torn leaflets, remove or rebuild tissue to allow the valve to close properly or reinforce the valve’s base.

Tricuspid valve regurgitation is often treated surgically with an annuloplasty ring – either tissue or synthetic – that supports the annulus, the tissue that forms a ring around the base of the valve leaflets.

Replacement: If it’s not possible to repair a damaged tricuspid valve, you might need a replacement valve. It’s often a biological (usually animal) tissue valve, but synthetic (mechanical) valves are also available. Your doctor will decide which is best for you.

Biological valves can last up to 20 years, so younger patients will likely need another valve as the replacement deteriorates. With a mechanical valve, though it can last a lifetime, patients must take blood thinners for the rest of their lives to avoid potential clotting and stroke.

Doctors have some options for tricuspid valve replacement: open-heart surgery (with an incision through the breastbone up to 8 inches) or a less invasive technique using a 3-inch incision through the sternum or a small incision on the right side.

Another minimally invasive procedure places a new valve within the existing valve delivered to the heart via a catheter inserted through the groin.